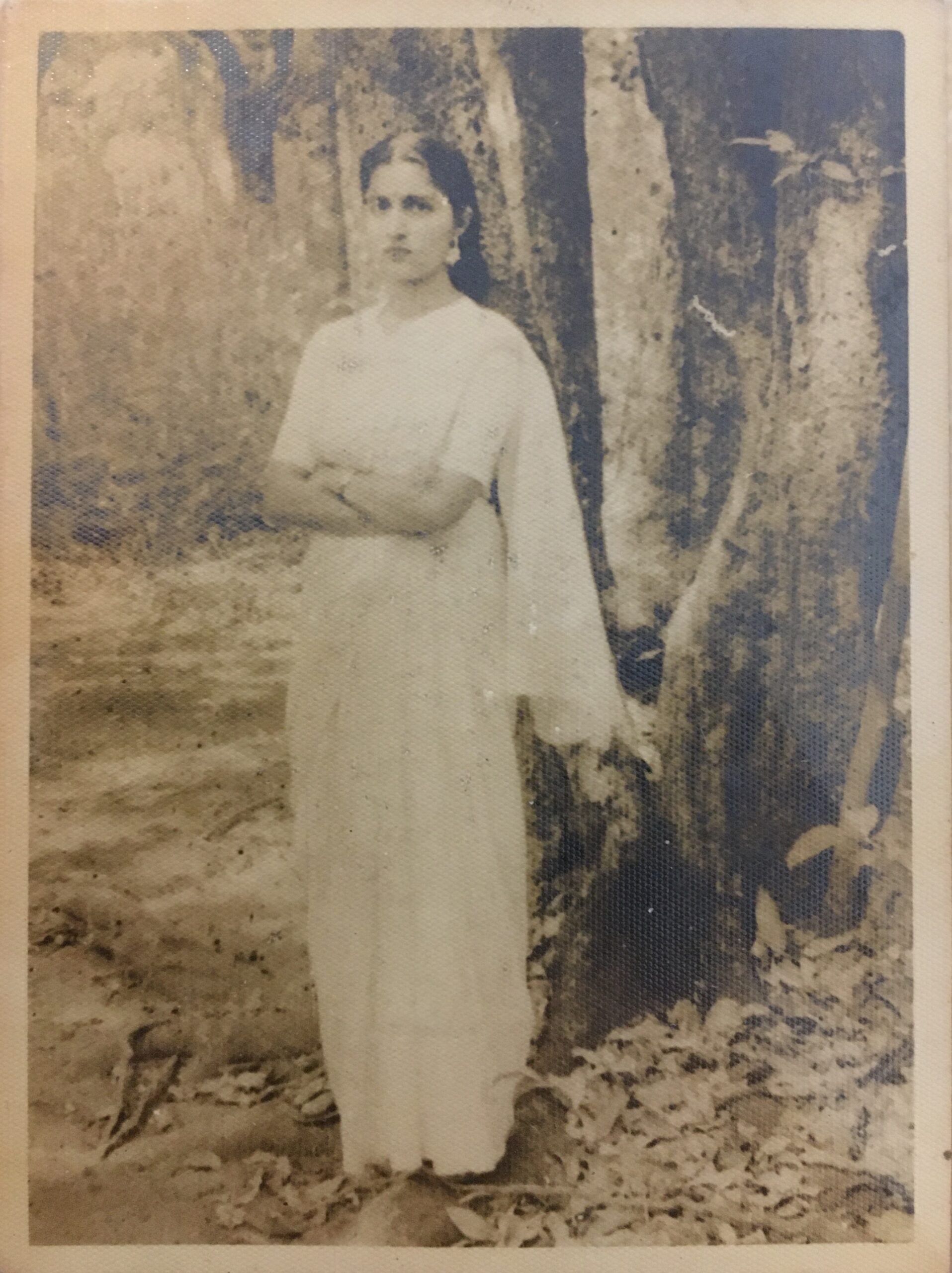

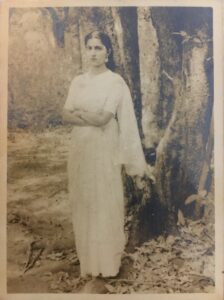

Ada and Armida (right, and lower center) with their mother Matilda and cousin Maria de Luz at their home in Dharwar, Karnataka, mid 1940s

“To me Dharwar was heaven”, says Armida. “Full of flowers, trees, butterflies and birds. That is where my heart is, to tell you the truth. The way my father brought us up, we believed that home is not a fixed place, but anywhere that there are people, and things to do.”

Ada and Armida, the two sisters of the Menezes family from the village of São Mathias – a small hamlet on the riverine island of Divar, recount their childhood outside of Portuguese controlled Goa where their father Armando Menezes raised them to believe it was as important to call one’s self Indian as it was to be Goan. “How could we not ?” says Ada, who like her younger sister spent her formative years in Dharwar, Karnataka in the decade before Indian Independence around spokesmen of the Gandhian movement – writers, poets and educators of Karnatak College of which their father was one.

In the early 1900s Dharwar wasn’t really a city, but a little township away from the rest of the world, snuggled on seven hills, with a temperate climate and houses with beautiful gardens and trees. The township became an important educational centre to the pre-independence state known as the Bombay Presidency – the large expanse of administrative land to which the British-controlled regions of the Konkan and North-Western Karnataka belonged.

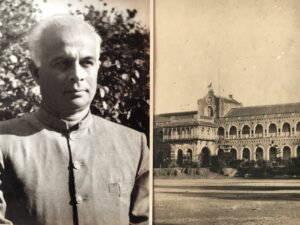

Professor Armando Menezes and a photograph of Karnatak College of which he was Vice Principal in the year 1947

Karnatak College

At the heart of the community, and the lives of Ada, Armida and their five brothers was Karnatak College – an immersive world of progressive thinkers and educationalists which left its mark on them from the early years. Their father Armando Menezes taught English Literature. Armando was a teacher by profession, and a poet who wrote and spoke out passionately for the cause of Goan and Indian independence from Portuguese and British powers respectively. He was also a translator of works of Bhakti Poetry (Vachanas) from Kannada to English. Ada and her siblings grew up around a father who was in frequent correspondence with like minded poets and writers. They were fostered in the shadow of the independence movement, and spent time with their father’s acquaintances and friends – poets such as KD Sethna and Harindranath Chattopadhyay, and Sarojini Naidu, the famed Indian political activist. The literary and political fervour of Karnatak College influenced them not only to be writers, but also to participate in the country’s freedom movement from a very young age.

At their home in Dharwar with their fifth child and newborn son, Ignatious

An Open Home

Beyond the college, there was the home kept by their mother, Matilda, that defined their fondest memories of childhood. Remembering her these days, Armida says “We had no physical comforts such as cars, radios, or even cooking gas; but we had the luxury of time. It was a precious childhood. We went on cycling picnics together to pick up karvanda berries. We played badminton. Or we formed a sort of club in the evenings where people met and sang. It was a different world. Instead of saying I’m a Goan, I would rather say I’m a Dharwarian.The links we have to Dharwar are strong ones.

Despite living on a professor’s salary, the type of environment Ada and Armida’s parents brought to the house was one of constant welcome. Theirs was an open home. “People just came in. Boys and Girls from the hostel came in for meals. So many foreigners – from all parts of the world, would come over too. Often my brothers Lenny and Louis would bring home travellers they had just met, to have a meal. Anybody could walk in; everybody was a friend. People who just arrived in Dharwar from Goa were told they could find a meal or two at our home. This is the kind of house we grew up in. Somehow, my mother always managed to provide.”

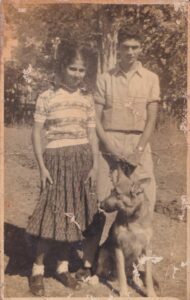

College Days: Armida and her brother Leonard with the family dog, Trevor

Ada in her bharatanatyam costume, studio portrait mid 1940s

Bharatanatyam

Ada’s childhood was marked by an obsession with Indian classical dance. From a very young age, she sought out Bharatanatyam as her expression of choice. Though Dharwar was then famous as the southern epicenter of Hindustani music – a crucible for drama, dance and music, Ada recalls that it had been incredibly difficult to find a teacher. Eventually her mother found a dance master in a neighbouring town and Ada began a journey in the artform. She developed a passion and skill for it which would take her to many performances across Karnataka and Goa. Growing up in a large catholic family, she used Bharatnatyam as a way to assert her individuality, and also to take refuge from the anxieties of adolescence.

[Ada, a dancer on on and off stage used the garden as a setting for practice and performances]

Young women’s tug of war, part of the festivities on Independence day 1947, Karnatak College, Dharwar

A Tale Of Two Independence Days

Remembering the momentous day in 1947 that India woke to independence from the British, Ada, then seventeen years old, talks enthusiastically of the celebrations that took place on the Karnatak College grounds – the white saris and kurta-pajamas of jubilant women and men in the march past, the games and sports, the unfurling of the Indian flag and a moving address delivered by her father who was then the Vice Principal.

Armida describes that day very differently. “I was only 4 years old, and I remember just two things. First, it seemed to rain sweets from the sky…which must have been sprinkled from helicopters now that I think about it, and I remember my father’s grasp very tight on my hand. He was standing very still and shaking with tears, and he could not seem to stop them”.

Seven years later, on August 15th, 1954, Ada was invited by the office of the Portuguese Viceroy to perform a Bharatnatyam piece in Goa in honour of India’s Independence. As a free Indian, Ada went back to her unliberated homeland, to celebrate India’s freedom from colonial rule. She performed on a stage setup in an outdoor venue in the center of Panjim City. Years later, in a twist of fate, that venue came to be known as Azad Maidan (Freedom Field) once Goa was liberated in 1961.

The irony of circumstances of her arrival and visit to Goa that year continued into her departure. On her way back to Dharwar that evening, Ada helped smuggle her aunt Alda out of Goa in the back of her car to protect her from the Portuguese Police, since Alda’s husband Niclao Joao was wanted for dissenting against Portuguese rule, which put her safety in question. Ada remembers the fear that had gripped her at the state borders when their car was inspected. However, they made it safely across to Dharwar.

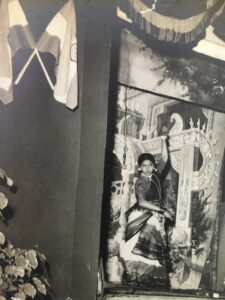

Ada performing at the Indian consulate celebrations in Panjim at the outdoor venue that later came to be known as Azad Maidan, Indian Independence Day 1954

Exiles

Nicalo Joao Menezes, the man in question, had been forced to flee Goa, a fugitive on the accusation of possessing “seditious” pamphlets. His was an arduous journey on foot through forests of the Western Ghats and across rivers to reach the bordering state of Karnataka. It was to his brother Armando’s home in Dharwar that he went to stay out his exile. His wife Alda joined him there shortly after, having escaped in a car with the help of her niece. It would be a while before they would all return to their ancestral home on the island of Divar. For his own writings against the Portuguese occupation of Goa, Armando Menezes received his punishment by being blacklisted by state authorities so he could not visit Goa for over a decade.

Armida recounts. “We loved Dharwar, but Goa was always in the backdrop; ever present. When my father was blacklisted, there was an entire ten years of my childhood through which I did not see Goa. I was the youngest, and all the others had spent many summers in Divar. I had not. In those years, we never left Dharwar. I spent ten summers there. Perhaps that is why I grew so fond of it”.

In his essay titled “The Cradle Of My Dreams”, Armando Menezes worte of this particular feeling of estrangement:

“My poetry, as one critic said, was a poetry of exile – as so much of Goan poetry is; another, more perceptive perhaps, said it was the poetry of the Island of Divar. Both were right, though one thought only of the mood, the other of the imagery. I have written a good deal about Goa: though I have written a great deal more as a Goan.

I have been stirred by its humours as well as by its tragedies…For its sake I have courted arrest and exile- and the chargin of an electoral defeat. For its sake I have earned admiration abroad and enemies at home.”

As it often is in the perception of Goans, theirs is a story of a kind of breach – a state of being outside of that with one holds dearest, of being unsettled, yet, also settled between two places. For the Menezes it played out back and forth over two colonial lands – their country, and their homeland.

Today, while Ada and Armida live in Bombay, the sisters feel a strong connection to Goa, to Dharwar; to their village of São Mathias, and the family home, yet – in their story they illustrate that one’s sense of self need not be exclusive to ancestry, nor to any one place.

Nishant Saldana

Images Courtesy The Menezes Archive, São Matias, Goa. See the entire collection here